Ibero-America, the 2030 Agenda and SSC for and/or with indigenous peoples

Although the region has certain experience in Bilateral South-South Cooperation for and/or with indigenous peoples, there is still much to be done in this sense.

“Indigenous peoples have suffered from historic injustices as a result of, inter alia, their colonization and dispossession of their lands, territories and resources, thus preventing them from exercising, in particular, their right to development in accordance with their own needs and interests” (UN, 2007).

Although the countries of the region have been making progress to recognize and protect their rights, “indigenous peoples are still one of the most socially, politically and economically excluded and neglected sectors of the population in Latin-America” (ECLAC and FILAC, 2020, Pag. 15).

On the other hand, indigenous peoples play a key role in climate change mitigation and biodiversity conservation -particularly agro-diversity – through their knowledge, practices and uses of nature. As a consequence of the above, protecting their territories is no longer only essential for them, but for all humanity.

How has SSC responded to these challenges? In the document South-South and Triangular Cooperation and Indigenous Peoples, Zúñiga states that “South-South and Triangular Cooperation for or with indigenous peoples has been essentially absent from the definitions of public policies on cooperation in most of the countries of the Ibero-American community” (Zúñiga, 2022, Pag. 30). Although not specifically aimed at indigenous people, several South-South and Triangular Cooperation instruments can support this type of initiatives. However, in Zúñiga’s perspective (2022), the subject is not being addressed on the basis of a specific strategic guideline.

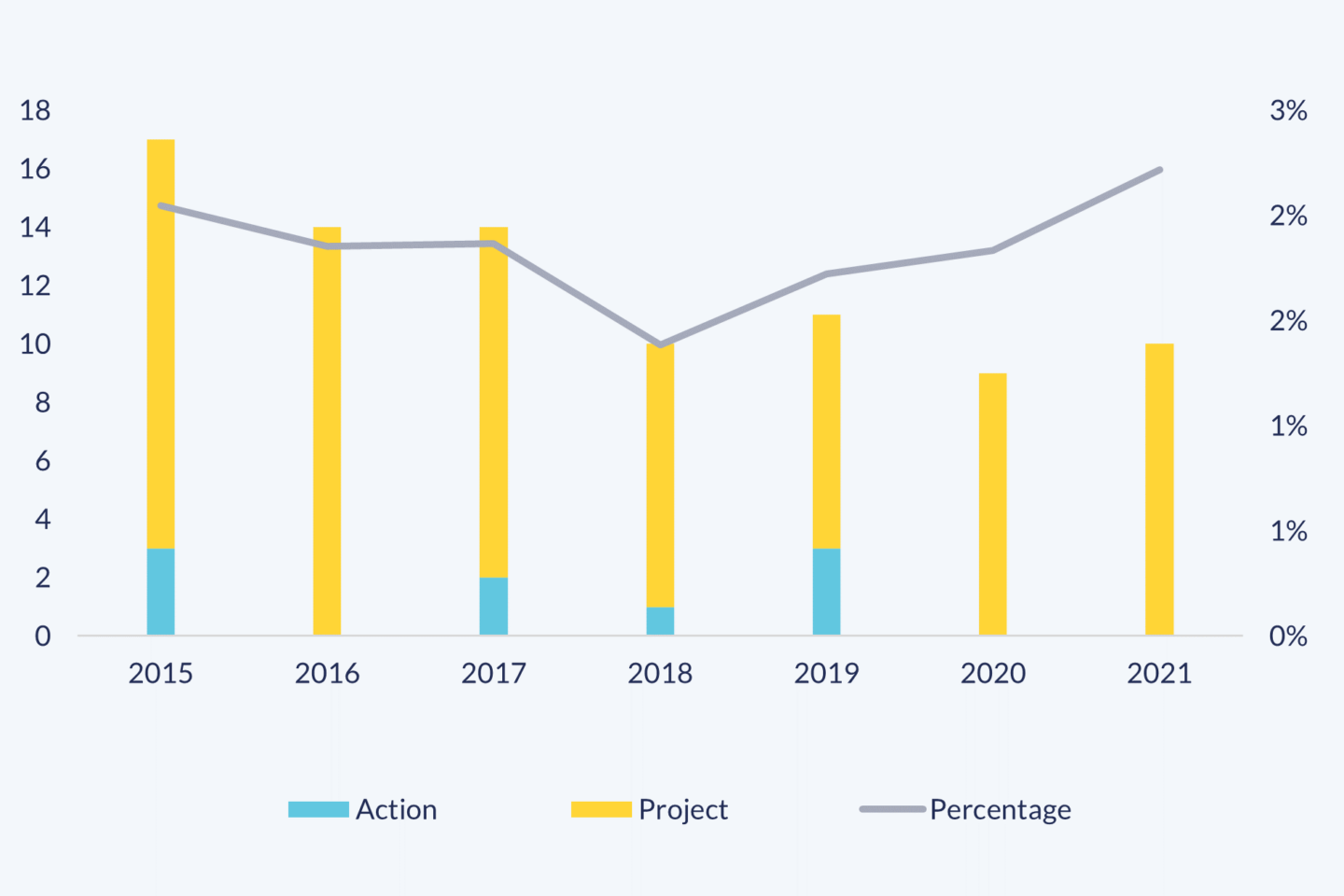

Forty-eight Bilateral SSC initiatives were implemented in Ibero-America between 2015 and 2021 for and/or with indigenous peoples (39 projects and 9 actions), accounting for 2% of the total. This percentage is only slightly higher than that identified by Zúñiga (2022) for all South-South and Triangular Cooperation between 2006 and 2019 (1.2%). Of these, two thirds correspond to what the author calls “initiatives for indigenous peoples”, i.e., those that have indigenous peoples as the only beneficiaries. The rest are initiatives “with indigenous peoples”, which explicitly include them among their target population, but together with other groups.

As the first graph shows, Bilateral SSC initiatives for and/or with indigenous peoples in Ibero-America have fallen in the analyzed period: from 17 in 2015 to 10 in 2021, although this drop is smaller if only projects are considered. Its proportion over the total annual Bilateral SSC initiatives reached its minimum in 2018 (1.4%), but steadily increased thereafter, including in the pandemic years, with a maximum of 2.2% in 2021.

Graph 1. Evolution of Bilateral SSC initiatives in Ibero-America for and/or with indigenous peoples, by type and percentage over the total. 2015-2021

In units and percentage

SEGIB based on Agencies and Directorates-General for Cooperation.

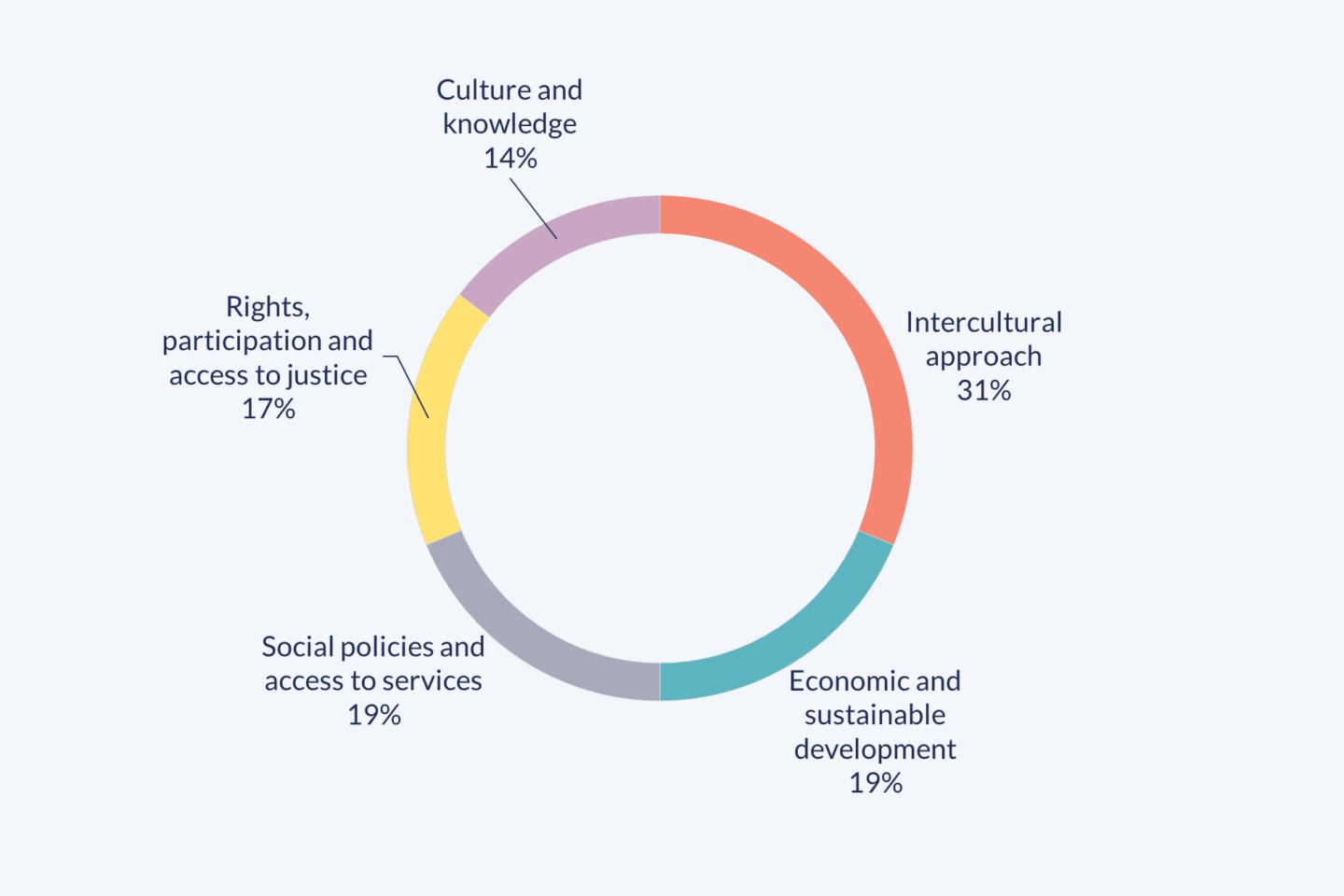

As for the topics that were addressed (see the second graph), 31% of the initiatives can be grouped considering an Intercultural approach to public policies (mainly health and intercultural education), but also based on their cross-cutting impact on public management and planning. Economic and sustainable development issues followed as well as Social policies and access to services, each with almost one-fifth of the total.

In terms of Rights, participation and access to justice, some initiatives focus on electoral participation, but also on participation in the design and execution of public policies, the right to autonomy and governance, and the right to defense.

Finally, and classified in Culture and knowledge, it is possible to identify projects and actions related to safeguarding the intangible cultural heritage of indigenous peoples, indigenous languages and ancestral knowledge.

Graph 2. Main topics addressed by Bilateral SSC initiatives in Ibero-America for and/or with indigenous peoples. 2015-2021

In percentage

SEGIB based on Agencies and Directorates-General for Cooperation.

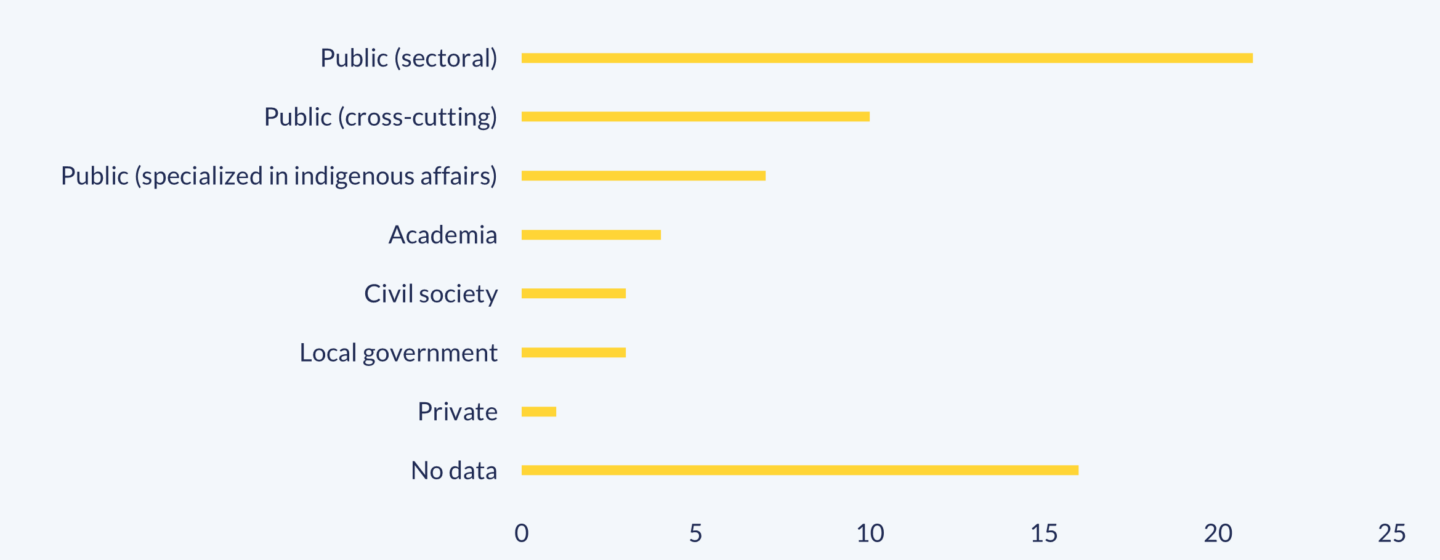

The third graph focuses on the type of stakeholders that participated in the initiatives. In this sense, as the graph shows, indigenous organizations only participate in 1 initiative out of 48, while most of them are implemented by public institutions, whether sectoral, cross-cutting or specialized in indigenous affairs. Academia, civil society, local governments and the private sector also participate in this cooperation although to a much less extent.

Graph 3. Type of stakeholders that participated in Bilateral SSC initiatives in Ibero-America for and/or with indigenous peoples. 2015-2021

In units

Source: SEGIB based on Agencies and Directorates-General for Cooperation.

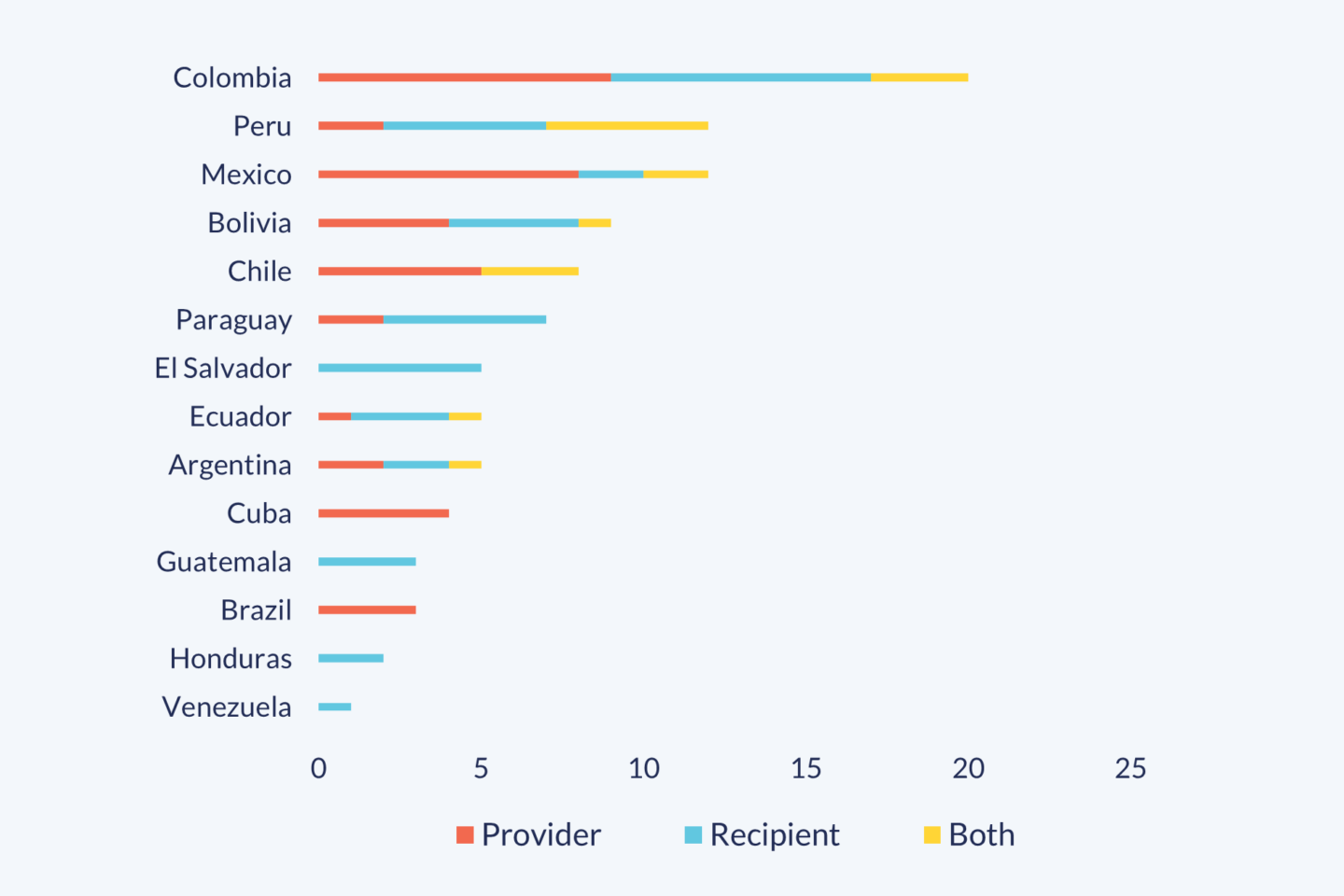

In turn (see fourth graph), 14 countries in the region have engaged in Bilateral SSC initiatives for and/or with indigenous peoples between 2015 and 2021. Colombia stands out with a completely bidirectional profile, since it equally participates as provider and as recipient. These 20 initiatives represent 3.7% of the total Bilateral SSC this country promoted with Ibero-America.

Peru and Mexico follow, the former with a dual profile that tends to receive technical assistance, and the latter with a predominantly provider profile. These two countries participate in almost one quarter of the initiatives.

Bolivia, Chile and Paraguay have also been active in this type of cooperation. Chile has mainly participated as provider or in bidirectional initiatives, while the other two have had a more varied profile. In Bolivia’s and Paraguay’s cases, these exchanges represent 3.8% and 3.9% of the Bilateral SSC initiatives in which they participate during the period in Ibero-America, a proportion that almost doubles the regional average.

Graph 4. Countries’ participation in Bilateral SSC initiatives in Ibero-America for and/or with indigenous peoples, by role. 2015-2021

In units

Source: SEGIB based on Agencies and Directorates-General for Cooperation.

According to Zúñiga (2022), this type of SSC can become an essential instrument to bridge the gap between the recognition of indigenous peoples’ rights and their systematic violation in practice. Indigenous peoples must necessarily be included in political-technical dialogues on SSC and Triangular instruments and initiatives that are specifically directed at them or include them as part of their recipients.

August 2023

***

Source: SEGIB based on Agencies and Directorates-General for Cooperation, ECLAC and FILAC (2020), UN (2007) and Zúñiga (2022).